Proteins are made of a chain of 20 amino acids, and there are nine essential amino acids that we, humans, cannot synthesize; therefore, we must eat food to fulfill those needs.

I am here to tell you that you could absolutely get all your amino acids (note that I didn’t use “proteins” here) from eating plants. I am here to solve the myth of “incomplete proteins” that plants are often mislabeled or misunderstood. “Incomplete Proteins” simply means that the ingredient may be low or lack in one of the nine essential amino acids (eg. lentils are low in methionine, Brazil nuts are low in lysine). In order to obtain all the essential amino acids for our body, we need to eat a variety of fruits and vegetables to pool enough amino acids to form proteins. Classic pairing such as beans and rice, corn and beans, and legumes and nuts provide the necessary amino acids intake. As a chef, I love pairings. Pairing food gives me the opportunity to explore flavors and texture; broccoli (my constant obsession) is sweeter if cooked with garlic or chili. Lentil is more savory if paired with walnut. Finally, rice is sweeter if eaten with savory beans.

My walk through a rice paddy field in Taiwan

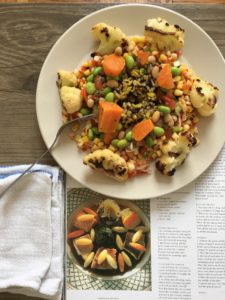

Here’s a recipe of Italian beans and rice that could get you started on completing-your-proteins from eating through the veggie aisles.

1 large carrots, cut into bite size chunks

1 medium onions, diced to your preference

5 cloves garlic, sliced thin or minced

3 tablespoons of canola/vegetable oil

1 can of great northern white beans or cannellini beans (canned beans has its benefit in its unique texture), or you may soak some beans overnight and cook them fresh the next day

½ cup of edamame (optional)

2 sprigs of thyme leaves

1 teaspoons of salt, or more to adjust seasoning

½ teaspoons of ground black pepper, or more to adjust seasoning

pinch of cayenne pepper (optional)

1 cup of your favorite rice, cooked (my choices are a mix of short grain brown rice, jasmine rice, and wild black rice)

- Set a pot on medium high heat and add oil, once the oil starts to shimmer, add your carrots, onions, and garlic. Season with salt and black pepper. Cook the onions and garlic until fragrant and soft. Carrots will be stewed and softened in the next step.

- Add thyme to the pot and cook until fragrant, and then add enough water to just cover the carrots. Cover the pot, bring it to a boil, and turn the heat to medium low. Simmer the carrots until soft, but not mushy. Bite size carrots will take less than 10 minutes to soften.

- Add the can of white beans and leave the pot to simmer for another 2 minutes to thoroughly heat the beans.

- Turn off the heat and add edamame. Cover the pot with a lid for 2 more minutes to heat up the edamame with its residual heat.

- Serve your Italian beans with your favorite side of rice. Add freshly chopped parsley and mint, and a squeeze of lemon to brighten up the dish, or a pinch of cayenne pepper will wake up your palate and help you enjoy a pint of IPA.

Rustic Italian beans and rice

Last but not least, why eat multiple plants when you could get all the amino acids from a piece of meat? Animal proteins have higher ratios of amino acids that contain sulfur, which is converted to sulfuric acid when digested by humans. In order to balance out the acidic condition, our bodies work harder to keep us alive, alert, and sexually active, as I am told.